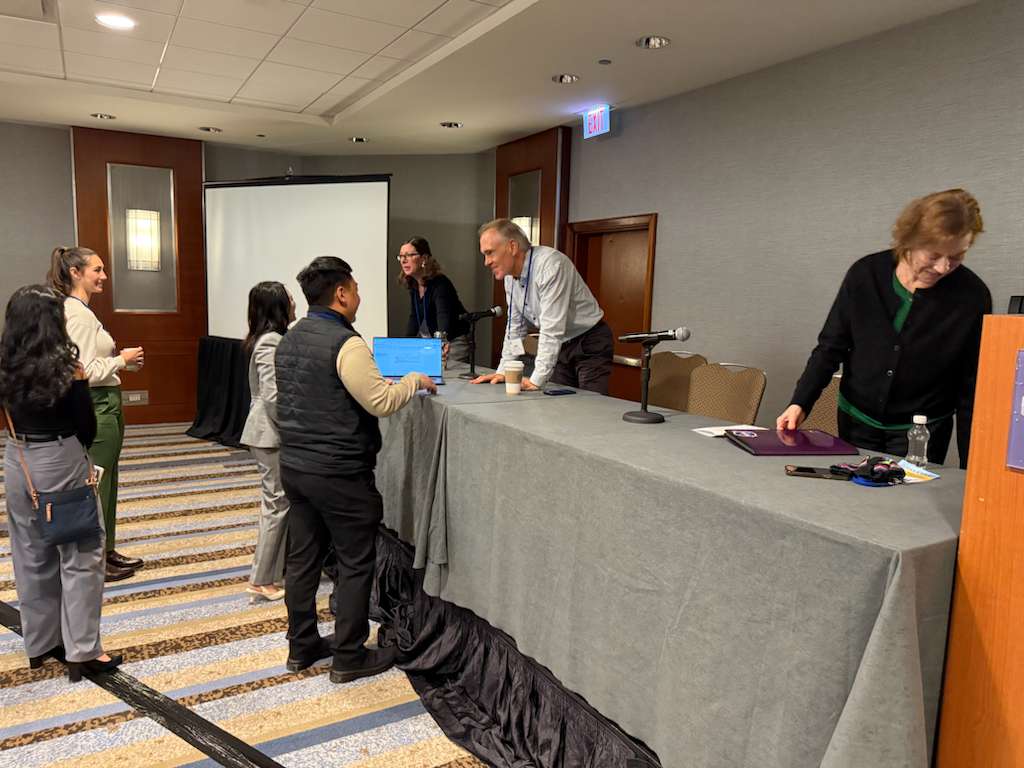

Panel recap from HFES ASPIRE 2025

The Aerospace track started ASPIRE ‘25 with this first panel, moderated by Kathleen Mosier (San Francisco State University), and bringing together Leia Stirling (University of Michigan) and John Lee (University of Wisconsin–Madison) to discuss how NASA’s Human Capabilities Assessments for Autonomous Missions (HCAAM) program is exploring the future of autonomy in long-duration spaceflight. The HCAAM program brought together 7 universities that conducted controlled lab experiments in their home institutions as well as in NASA’s space analogue environment for long-term mission — HERA.

Although Jessica Marquez and John Karasinski from NASA Ames were unable to attend due to the government shutdown, the conversation gave a rich look at how human factors research is shaping NASA’s vision of astronaut autonomy.

What does “autonomy” really mean in space operations?

Leia: The term “autonomous” is often misleading—it suggests something happening without people. But in reality, autonomy in space always involves a human element. “There will always be someone monitoring, helping, and making sense of the decisions,” she said. “It’s not about replacing people, it’s about managing risk and defining what information people need to know—and when.” Leia emphasized the importance of designing interfaces that provide the right amount of transparency, sometimes more, sometimes less, depending on the mission phase and the situation’s complexity.

John: Autonomy isn’t just about machines acting independently—it’s also about people being allowed to act without constant oversight. “It’s mostly autonomy of the crew—making decisions removed from the organization they’re part of,” he said. On long-duration missions, astronauts can’t rely on Houston to manage every detail, especially with communication delays or when systems fail. He recounted an astronaut’s story from training: before the mission, the astronaut recorded himself performing procedures perfectly as “Smart Steve.” Later, in space, he’d rewatch those videos as “Dumb Steve” to remind himself how to do it. “That story captures the essence of autonomy—translating training into action when no one is there to help.”

How are human factors researchers supporting autonomous operations?

Leia: Her work focuses on human–robot teaming, where one robot operates inside the habitat and another outside. These systems are designed to monitor astronaut readiness before extravehicular activity. “The virtual assistant doesn’t perform every task, but it can help find the root cause of a problem based on its knowledge,” Leia explained. “The challenge is that there are always root causes the system wasn’t trained on. We have to ask: what context is built into the system—and what isn’t?”

Autonomy in space always involves a human element. There will always be someone monitoring, helping, and making sense of the decisions.

Leia Stirling

John: His team studies how astronauts trust automation and each other when communication with Earth is cut off. “Risk is central to trust,” he noted. “It’s about how much you’re willing to rely on another party.” That’s not an easy thing to measure in a small analog environment. “Each HERA mission has four people living together for six weeks. Even after seven missions, we’re still working with a small sample.”

Trust seems to be a recurring challenge. What have you learned about it?

John: His research has led to some fascinating distinctions—especially between convergent and contingent trust.

“In a convergent system, everyone’s trust tends to stabilize around a common point,” he explained. “But in a contingent system, people start at the same place and diverge over time. Two astronauts might begin with the same moderate trust in a system—one has a bad experience and loses trust, while another has a good one and becomes more confident. Their trust bifurcates.”

I’ve been studying trust since my dissertation and I’m not sure I understand it much better now!

John Lee

This divergence challenges assumptions that more experience always leads to consensus. “With a small number of missions, contingent behavior can make it hard to predict when trust will suddenly go off the rails,” he said. To address that, his team is modeling how trust evolves and developing systems that can detect and recalibrate user trust in real time.

He added that “people don’t always prefer what works best.” For example, astronauts testing augmented reality tools often preferred the new tech—because it felt futuristic—but performed worse with it than with a traditional screen. “The customer isn’t always right,” John said. “The goal is balancing preference with performance.”

What are the challenges in measuring human performance remotely?

John: Measurement has been a human factors challenge for decades. “We’ve been struggling to measure things like situation awareness, workload, and trust since the 1980s,” he said. In HERA, researchers recorded and analyzed more than 2,500 conversational turns to infer trust levels based on language patterns. “It sort of works—but it’s noisy,” he admitted. “So to the question of how we measure performance remotely—the honest answer is: we’re still figuring it out.”

Leia: In simulated environments, she said, you can define what counts as the “right” answer. But as missions become more flexible, multiple paths can lead to success. “We need to recognize that people can reach correct outcomes in different ways. Our measurements need to capture that complexity.”

What lessons from HCAAM can apply beyond space?

John: “Humility is a major lesson,” he said. “You think you have a great system—and then it fails in unexpected ways.” His research also highlights the importance of dynamic calibration of trust, allowing systems to measure and adjust how much users rely on them. Another takeaway is the idea of bidirectional alignment—making sure humans and AI share not just goals, but also values and understanding.

In the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, maybe HAL was right—the mission should take precedence over the individual. So where do you align? With the billions on Earth, or the few people in the spacecraft?”

John Lee

That question of alignment applies equally to autonomous vehicles on Earth, he suggested. “Do you align automation with collective traffic flow, or with the driver’s individual goal that might go against the traffic?” John Lee is now exploring that question with NSF-backed project.

What’s next for human factors research in autonomy?

Leia: Collaboration is key. “We can’t work independently anymore,” she said. “Human factors, systems engineering, and AI researchers need to work together to understand the models and their limitations.” She emphasized that effective scenarios and data sharing are crucial to move forward.

John: He urged human factors professionals to deepen their understanding of the technologies they study. “With large language models, for instance, the fine-tuning process shapes how assertive they sound—and there’s no way for them to express uncertainty. That design decision affects user trust and perception.” He also reminded the audience that even mundane details—like microphone setup or shared meals—can shape crew dynamics. “The small stuff matters,” he said. “Sometimes, what keeps a team aligned isn’t the system design—it’s dinner together.”

Closing thoughts

The discussion revealed how the next frontier of autonomy isn’t about removing people from the loop—it’s about designing relationships of trust, adaptability, and shared purpose between humans and intelligent systems. As Lee put it, “The goal is robustness. The system might not be perfect in normal conditions, but when things go wrong—that’s when it has to shine.”

Leave a comment