Panel recap from HFES ASPIRE 2025

What happens when weather conditions start slipping from marginal VFR to IFR—would you still take off and fly? That opening question set the tone for a fascinating morning panel at ASPIRE 2025, where leading human factors researchers discussed how general aviation (GA) pilots make sense of uncertain weather forecasts. Moderated by Barrett Caldwell (Purdue University), it invited three other panelists:, Beth Blickensderfer (Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University), Michael Dorneich (Iowa State University), and Brandon Pitts (Purdue University).

Each presented a different angle of research aimed at helping GA pilots make safer, smarter weather-related decisions.

Barrett Caldwell — Understanding the gaps in cockpit weather information

Barrett opened with insights from the PEGASAS Center of Excellence, a decade-long research collaboration focused on weather technology in the cockpit. His work explored how information visibility and accessibility influence a pilot’s go/no-go decisions.

“Most of the uncertainty,” he explained, “comes from the lack of accurate weather data between two airports.” While airports are equipped with weather sensors, vast stretches of airspace—especially mountainous or remote regions—lack real-time data. “There’s no airport on the side of a cliff,” Barrett said. “And that’s where things can go wrong.”

He illustrated how this data gap has led to accidents, such as helicopter tour in the Grand Canyon encountering dangerous eddy flows. His research also highlighted that pilots tend to rely heavily on personal heuristics and experience when faced with incomplete information. That intuition can be powerful—but also risky—if not supported by the right situational awareness tools.

Most of the uncertainty comes from the lack of accurate weather data between two airports. There’s no airport on the side of a cliff—and that’s where things can go wrong.

— Barrett Caldwell

The PEGASAS program has produced several cockpit demonstrators that visualize weather latency and state information, helping researchers study how pilots interpret risk and uncertainty. Some findings were unexpected, Barrett noted: “Even experienced pilots often showed insufficient skills in predicting how uncertainty evolves during flight.”

Beth Blickensderfer — How GA pilots brief for weather

Download Blickensderfer’s presentation online

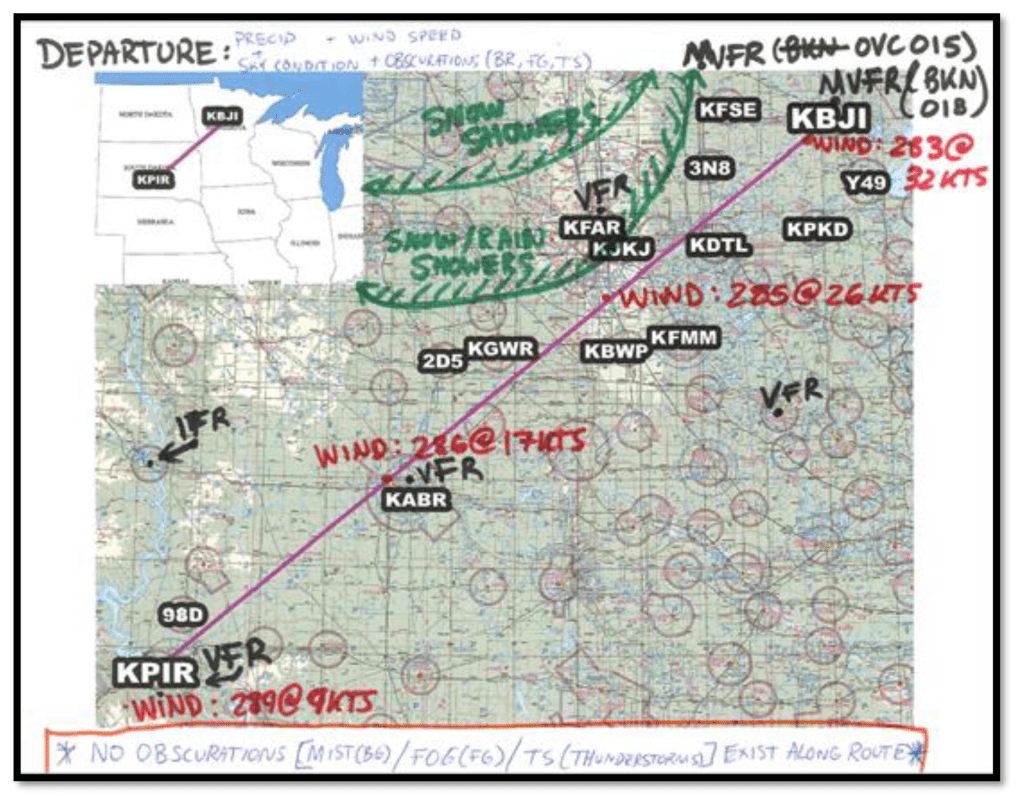

Beth presented a controlled study that examined how GA pilots conduct preflight weather briefings, comparing traditional Flight Service Station (FSS) calls with modern self-briefing apps similar to ForeFlight.

Her experiment crossed two factors—self-briefing (yes/no) and FSS call (yes/no)—to create four groups. Each group planned two flight scenarios: one with marginal VFR deteriorating to IMC, and another with potential icing. Both were legal flights, but with uncertainty built in. Scenarios were prepared in advance. For the FSS, a weather specialist recorded the brief based on the weather scenario and participants listened to it. For the self-briefing, the research team saved screenshots from ForeFlight a day that experienced weather like the one from their scenario. Then, they created a “canned” version with the screenshots and maps that participants used to review the weather predictions.

Pilots who used only the Flight Service Station had the best understanding of the weather. Those who combined FSS with self-briefing actually performed worse.

— Beth Blickensderfer

Most importantly, she revealed that the design of the app influenced how pilots did their briefing. Participants followed the order in which the app presented the maps, clicking through static weather layers in the same order every time.

Beth’s main takeaway was for pilots to have a strategy before starting the brief to review important information in the correct order. She also suggested that weather apps should embed this order when presenting their overlays to support pilot’s review.

Michael Dorneich — Bringing 3D weather to life through augmented reality

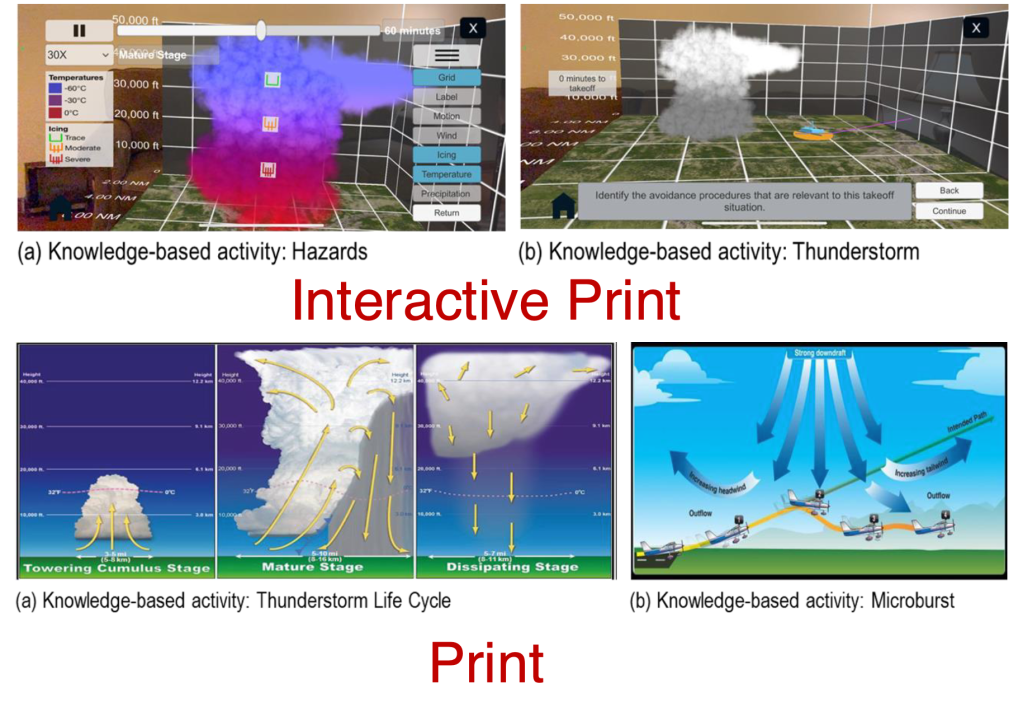

Michael shifted the discussion from decision-making to training. His team at Iowa State University has been using AR to help low-hour GA pilots visualize 3D weather phenomena—like convection, icing, or wind shear—that are often hard to grasp from 2D images.

Students learn about weather in ground school, but it can be months before they actually experience it in flight—we wanted to close that gap.

— Michael Dorneich

His group built AR modules for iPhones that overlay interactive 3D visuals on top of printed training materials. The results were promising: trainees showed higher motivation and stronger knowledge gains on fact-based tests.

However, when confronted with open-ended, scenario-based questions, performance dipped. “When pilots had to stop and make a judgment call, they started relying on visual cues and heuristics instead of the data,” Michael explained. “That’s exactly the kind of mistake we’d rather see happen in a simulator than in the air.”

To make AR adoption feasible, his team developed easy-to-use creation tools for instructors, allowing them to build new modules in minutes without coding. Instructors could drag and drop weather cells, define a flight path, and embed quiz questions—all within 17 minutes, he said. Main results of this work was recently published in the Ergonomics journal. The goal is to shift from tech-centric design to content-centric instruction, empowering educators to create their own immersive weather lessons.

Download Michael’s presentation with images and videos to see the AR training in actions.

Brandon Pitts — Automating pilot weather reports (PIREP)

Brandon closed the session by tackling Pilot Reports, or PIREPs. These reports provide real-time observations about turbulence, icing, and cloud layers—but filling them out mid-flight is cumbersome.

“Many GA pilots simply don’t submit them,” he said. “And yet, so many weather-related accidents could have been prevented with better situational reporting.” To address this, Brandon’s team is developing a speech-to-text system that automatically encodes spoken pilot reports into the official PIREP format.

His study surveyed over 460 GA pilots, collecting audio samples of how they would describe weather in various scenarios. The algorithm then transcribed those recordings into structured PIREP codes. Early results are encouraging, though noise remains a major challenge. “Our base model had about a 20% word error rate,” Brandon noted. “But when we added realistic cockpit noise, that jumped to 60%.” Even so, their deterministic encoder achieved 60–70% accuracy—an important step toward real-time PIREP automation.

Leave a comment